Happy Spring 2021! I took a break from teaching in Fall 2020 to get through the small, unimportant task of applying for postdocs 😉 but now I am back to teaching, and thus the hiatus on this blog is also hopefully over!

In Spring 2021, I am teaching linear algebra. While preparing for this course, I kept hitting a wall whenever I thought about my designated “lab” sessions. So what on earth is a lab?

At Emory, linear algebra and similar math courses are taught in two 75 minute sessions a week (normally Mon-Wed or Tue-Thurs), and then an extra 50-minute “lab session” (usually on Fridays) per week. The 75-minute sessions are led by the course’s instructor of record, usually a visiting or permanent faculty member, and the 50-minute sections are led by a teaching assistant, usually a graduate student. “Lab” is probably a misnomer, considering there isn’t any actual computing or laboratory work involved. In my undergrad, we used to call these “review sessions.” More on this later.

Graduate students also get to be instructors of record for courses, but usually, this is restricted to Calculus 1 and Calculus 2. Rarely, grad students also get to teach Multivariable Calculus, but in my five years here, I only remember one instance of this.

Well, things have changed this year. A couple of my grad student colleagues and I have wanted to teach linear algebra for a while now. This year, Emory granted our request and decided to run a grad-student-led cohort of Linear Algebra sections. This causes an immediate problem: they are unwilling to have a grad student TA for a course led by another grad student, which, you know, fair! The deal, thus, was that if we get to teach our own linear algebra class, we also have to teach the labs.

This is a pretty good deal, and so, of course, I was all for the opportunity. The only problem is: what on earth is a lab without a TA?

In order to figure this out, we have to ask, what really is the point of labs when there is a TA? I came up with the following reasons having a lab is nice:

- Students get to review the topics covered in class each week.

- They get to interact with a TA and maybe ask questions that they are hesitant to ask their instructor.

- They get to see a different perspective on the material, considering someone else is teaching it.

- Depending on how you run your labs, students might get to see different examples from what they would see in class.

- Even if the examples aren’t that different, it is good to have time set aside where you explicitly don’t cover new material. This might allow you to go more in-depth on the material already covered.

Those are most of the advantages of a lab that I could come up with, and I was struggling with replicating them in a lab without a TA. It bothered me that if I teach both the lab and the lectures, the course loses something. Also, less importantly, if I end my class on the day before the lab in the middle of a topic, it felt odd to say, “Well, you will see me again soon, but we will do something completely different instead of finishing this example/thought/discussion that we are in the middle of.”

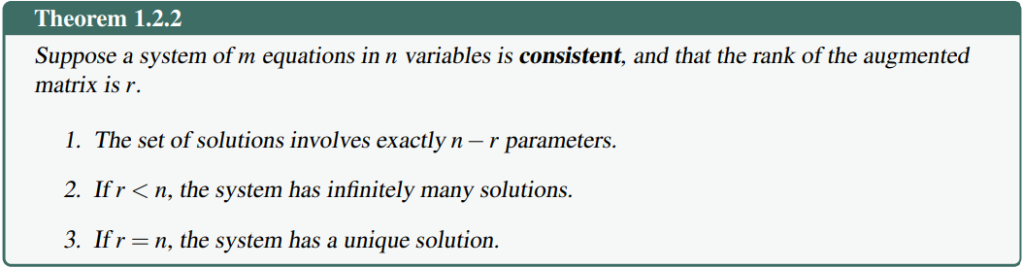

This Wednesday, I finished my class on Gaussian Elimination by giving them an example of a matrix to try on their own. In my next class on Monday, my goal is to teach them about the rank of a matrix and state the following theorem.

I decided to start Friday’s lab by quickly reviewing what we had covered during the week and solving the example that I had finished Wednesday’s class with. For the rest of the session, we worked on the following problem:

The rank of a matrix is the number of leading 1s in its row echelon form.

Give an example of a system of 3 equations in 2 variables such that the augmented

matrix has rank:

• 0

• 1

• 2

• 3

• 4

How many solutions does each of these systems have?

I solved part (a) together with them, soliciting answers to basic questions like: “How many rows would this matrix have? How many columns?” etc. Then I gave them some time to work through the other parts in pairs. Finally, we came together as a class to discuss it.

This worked exceptionally well. By the end of the class, they had concluded that rank has to be less than or equal to both the number of rows and the number of columns, and after a little prompting to compute the quantity “number of parameters + rank” for each of the cases where the system is consistent, they concluded on their own that the number of parameters + rank equals the number of variables. All before ever having seen the theorem!

As it turns out, I am a fan of the lab sessions. I don’t yet have a concrete plan of what I am using them for each week for the rest of the semester, but I do know for sure that it will be some combination of review and discovery!

Do you happen to teach a class with a similar lab structure? Do you have other ideas for me of ways to use the time most effectively? I’d love to hear some thoughts!